Electric cars can seem conceptually boring. There’s a motor, some batteries, and they all charge like your iPhone. But when that same technology is applied to a car that already has a combustion engine, things get a lot more exciting. Packaging the two powertrains together becomes more challenging, the choice of battery types and chemistries is much more critical, and the myriad ways electric power bolsters an ICE drivetrain becomes fascinating.

A prime example of two decidedly different approaches to achieve similar results is the Chevrolet Corvette E-Ray and the newly hybridized Porsche 911 GTS. Both cars have batteries with around the same capacity, both drivetrains use a single electric motor to drive the wheels, and both cars forgo a plug-in hybrid system. Beyond that, though, there are wonderful differences between the Corvette and Porsche. In traditional fashion, the E-Ray gets the job done with a surprisingly simple, cost-effective solution. Because the Porsche commands a higher price—even a base 911 costs more than a loaded E-Ray—its car utilizes a more complex solution: an F1-style electric turbocharger with no conventional wastegate. The differences between these two hybrid systems lie with the battery cells, or how and why each automaker decided to use their respective form factors.

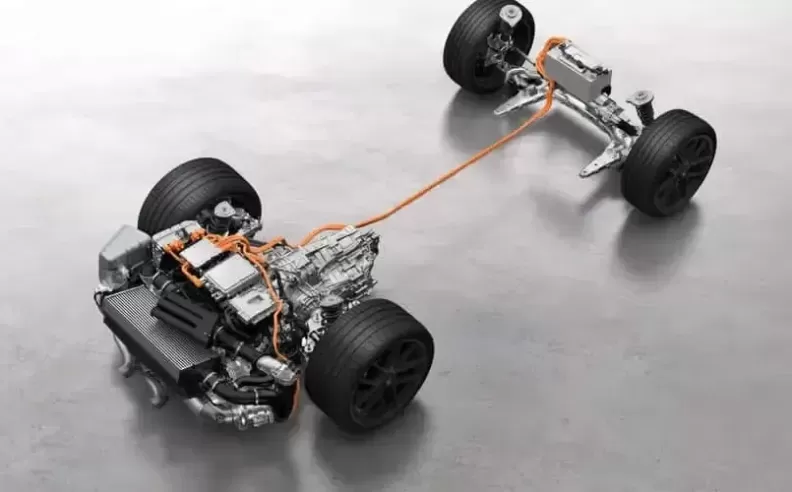

The Corvette’s lithium-ion cells are monsters. About the size of a squared-off dinner plate. Each can discharge an incredible 525 amps over a short period. Their size and chemistry enable that sort of current which is key to offering high power—and especially torque—at a relatively low voltage. The E-Ray has just 80 pouch-style cells, all wired in series, nestled into the spine of the chassis like a big candy bar. This 80S 1P configuration gives a 288V nominal figure for the whole 1.9 kilowatt-hour-gross system, of which far less is actually used. Lower voltage means lower motor speeds (generally), and higher current means more torque. The Corvette’s electric drivetrain puts out 160 horsepower (119 kilowatts). With the complete hybrid drivetrain—including the 495-hp 6.2-liter V-8—the total output is 655 hp.

General Motors wanted a small pack that could discharge high currents to drive the whole front axle with electric power alone. Their tunnel-mounted lithium Snickers bar is a great solution, providing ample torque and power without the need for a more complex system.

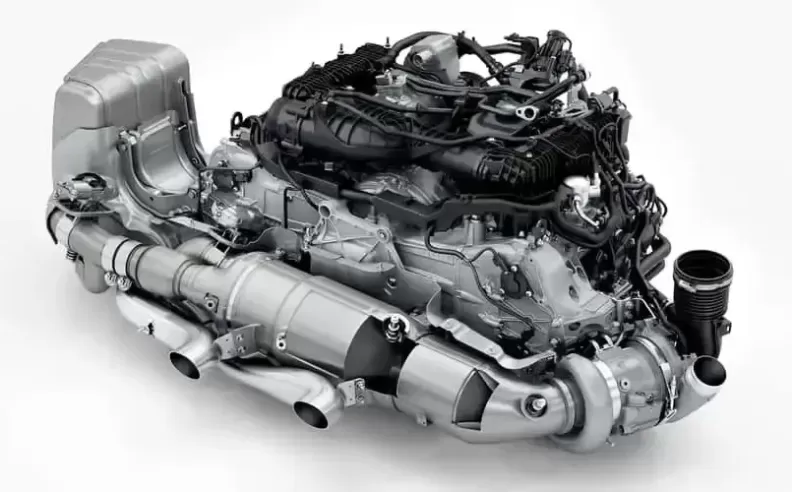

The Porsche’s battery is also 1.9kWh gross, and to be transparent, there’s still a lot we don’t know about it. It’s much smaller because the automaker uses cylindrical cells, likely 21700s, named for their diameter of 21 millimeters and length of 70 millimeters. The same form factor is used in Rivian’s current line of electric vehicles, some Teslas, and the Lucid Air. It seems like there are more than 200 of them stuffed into the tiny box under the hood, with between 96 and 112 likely wired in series. 112 would give a nominal pack voltage of 403.2V and a configuration of 112S 2P (there are definitely two groups in parallel). They are more energy-dense than the cells used in the E-Ray, but not more power-dense. Power density describes a pack’s ability to discharge high currents, and 21700 cells are generally inferior in this regard to larger pouches or prismatics. The Porsche’s system can likely discharge in the neighborhood of 67 hp (50 kW). But this is just an estimate. While we know the maximum power of the motor generator in the transmission (40kw), the electric turbo’s energy consumption is a mystery. The hybrid Porsche, including its 3.6-liter flat-six, produces 532 hp total.

Porsche, on the other hand, produces other hybrid vehicles using hardware that operates at 400V, like its active suspension systems. 400V is also better for use at higher motor speeds, which is a nice thing to have if you want to spin a turbocharger up to over 100,000 rpm. Higher current is not strictly necessary, especially if the 40 kW motor powering the rear wheels is already getting a speed reduction—and associated torque boost—from the transmission, as is the case in the 911. That electric turbo is an extremely interesting piece of engineering. If you’re familiar with how a conventional turbo works, you know that operating one without a wastegate is not a good idea. Well, it’s a lot of fun for a short time, at least. So how does Porsche pull it off? An electric motor is sandwiched between the hot and cold ends of the turbo. The rotor of this motor and the turbo shaft are coupled together, in fact, they're probably inseparable—they love each other very much.

Just like an electric motor in a conventional EV, this motor can either power the turbo with a rush of current from the battery or send power back the other way via regenerative braking. By braking the turbo shaft you can limit the speed of the turbine and compressor, therefore limiting the boost as well as creating energy in the process. Porsche says the car can harvest as much as 11 kW (15 hp) from the turbocharger alone. Formula 1 engines work the same way. How cool is that? For those of you familiar with turbo-compounding (not to be mistaken for compound turbos), that’s what this is.

As a side note, the turbo therefore has its own inverter which will likely dictate the turbine/compressor speed precisely throughout the entire range of engine RPMs and throttle positions. As such, turbo lag from the inertia of the turbine shaft isn’t a big worry, although I’m sure it was a big engineering consideration. The engine’s integrated starter-generator can extract power at idle like an alternator. The turbocharger can also charge the batteries under acceleration. In comparison, the E-Ray can only harvest energy while decelerating. Its “Charge+” function helps out in this regard, limiting discharge current and getting “free beer” at every conceivable opportunity. That’s what Corvette chief engineer Josh Holder calls regenerative braking energy. I have him on tape.

Why did they go different routes? Both automakers want different things, which happen to require around the same amount of energy. The E-Ray drives the whole front axle with electric power alone. General Motors wanted a small pack that could discharge high currents to do this. Their tunnel-mounted lithium Snickers bar is a great solution.

Porsche, on the other hand, produces other hybrid vehicles using hardware that operates at 400V, like its active suspension systems. 400V is also better for use at higher motor speeds, which is a nice thing to have if you want to spin a turbocharger up to over 100,000 rpm. Higher current is not strictly necessary, especially if the 40 kW motor powering the rear wheels is already getting a speed reduction—and associated torque boost—from the transmission, as is the case in the 911.

With both of these cars laid out on paper, it’s hard to understand why many are still opposed to performance hybrids. Both systems provide considerable power and capability. In the case of the Porsche, it gains just 103 pounds compared to the old non-hybrid GTS. The E-Ray weighs another 260 pounds as compared to a Z06 (still less than a new BMW M2!). If you’re so worried about the weight, kick out your passenger. Or in Porsche’s case, don’t check the option box for rear seats. They aren’t standard anymore in the 911.

None of this mentions other interesting ways to use electric current either, like powering engine accessories without a serpentine belt or adding downforce like the Gordon Murray T.50 with its huge tail-mounted fan. As battery technology improves, this tech will only get lighter, cheaper, and more exciting.

Wael is an automotive content writer specializes in creating written content for Motor 283. Producing a wide range of content, including blog posts, articles, product descriptions, reviews, and technical guides related to cars, trucks, motorcycles, and other vehicles, with an unprecedented passion for cars, and motorcycles.